Lindsey Naylor, Virginia Fall, Andrew Fox

Abstract

This article examines shortcomings and possible improvements to standard post-disaster recovery processes through the lens of recovery in Princeville, North Carolina, the oldest black town in the United States. Princeville has faced existential challenges since it was settled in the Tar River floodplain in 1865, most recently in 2016 with flooding caused by Hurricane Matthew. The article describes the power of place attachment and the trauma caused by place-based disaster. It points out that significant rebuilding typically begins a full three years into a standard recovery timeline. And it argues that in the midst of that recovery process, our identification of significant landscapes—i.e., landscapes worth protecting and restoring—is too heavily driven by the object-oriented standards of traditional historic preservation. This article describes work coordinated by North Carolina State University design faculty in partnership with the town of Princeville to supplement abstract, top-down recovery processes with practice that is landscape-based and interactive, that marks histories and establishes concrete symbols of ongoing life, and that promises to help displaced communities to build social-ecological resilience and to heal. This type of work will only become more vital as more communities face climate-induced disasters and the need to rebuild. By describing the impetus and possible impact of NC State’s post-disaster work with Princeville, this article seeks to start a conversation about how our recovery processes can better recognize the power of place and the role of the land as a vehicle for resilience and healing.

America’s oldest black town

Imagine what that would feel like to be told: ‘If you can just get to that rise by the Tar River across from Tarboro, if you can just get there, you might have access to freedom.’ And that hunger in your belly to get there, and your determination to stay there even when the rains come down, even when the mosquitoes come out. That is powerful.1

—Michelle Lanier, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, director of the Division of State Historic Sites

In late 1862, Union forces in the Civil War had taken control over much of eastern North Carolina, and their camps became beacons of possible refuge for the more than 350,000 North Carolina residents who were then living in bondage. These refugees of war and slavery began seeking out Union camps, building temporary settlements at their edges and often finding work with the Union army.

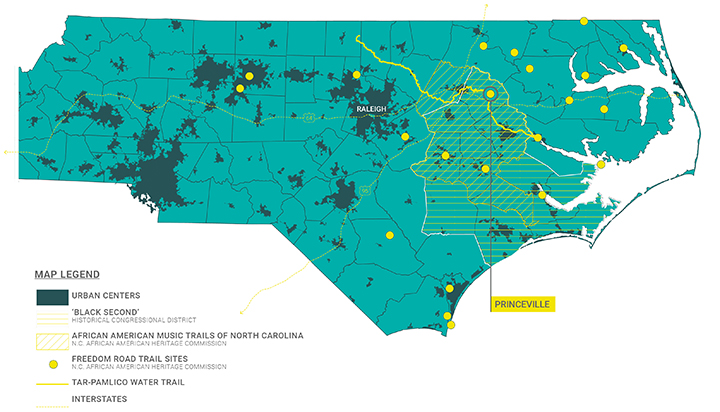

This is the beginning of the story of Princeville, North Carolina, founded in 1865 on land where Union soldiers had set up temporary encampment during their occupation of the Town of Tarboro, North Carolina (Figure 1).2 When many of those refugees decided to stay on the land after the war and to establish their own settlement, they named it Freedom Hill, after the high point on which a Union soldier had stood to share news of the Emancipation Proclamation. The white landowners of Tarboro saw the settlement as a source of inexpensive labor, and one of them agreed to sell floodplain land to the residents of Freedom Hill. The settlers built their own school, homes, and businesses. Freedman Turner Prince, a carpenter born into slavery, was one of the first to purchase land and construct permanent dwellings. In 1885 the North Carolina legislature incorporated the town, which its residents renamed Princeville in honor of Prince. Princeville’s 1885 charter makes it the oldest incorporated black town in the United States.

Like many self-sufficient black towns in the South, Princeville has faced existential challenges that are social, political, and environmental. A wave of violent white supremacy swept North Carolina in the late 1800s, an ugly populist backlash against the political and economic gains made by African Americans and their allies after the Civil War. Some of the white Tarboro residents who had seen Princeville as a conveniently sited source of labor now saw its very existence as a threat to their political and social order. In the early 1900s, white supremacists fiercely lobbied the state legislature to erase Princeville from the map, to revoke its charter and fold the town into Tarboro. Racist state and federal policies reinforced their efforts, making it difficult for Princeville to build and maintain its infrastructure and economy. In the early 1970s, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development assessed 19th-century Princeville homes that had been built in independence and freedom by people born into captivity; they deemed the houses of no historical significance and ordered their demolition. Many were replaced by double-wide manufactured homes.

Princeville lies almost entirely in the Tar River floodplain. The town was under water in 1887, 1919, 1924, 1928, 1940 and 1958 (Figure 2). Every time, Princeville residents cleaned up and rebuilt. In 1967, the US Army Corps of Engineers finished a levee along the Tar River designed to protect the town against 500-year floods. It worked for 32 years, until the double impact of Hurricanes Dennis and Floyd in 1999 left the town flooded for weeks. That event made clear that the levee to Princeville’s north, and the elevated US Highway 64 to its west, together created a dam so that when the Tar River rose high enough, its waters would seep around the edge of the levee, fill Princeville, and have nowhere to go.

Jesse Jackson came to Princeville in 1999 to bring national publicity to the plight of America’s oldest black town. The musician Prince donated to the cause. President Bill Clinton signed an executive order creating the “President’s Council on the Future of Princeville, North Carolina,” a convening of cabinet secretaries and other executive officials charged with protecting the town from future damage.

Sixteen years later, stormwater from Hurricane Matthew worked its way downstream, the Tar River rose, and its waters seeped around the edge of the levee, inundating Princeville again.

Sites of memory

In the dedication to protect critical and valued resources, climate change issues require that we be nimble and flexible, yet adhere to basic beliefs and ideals.3

—Robert Melnick, landscape architecture professor emeritus, University of Oregon

Global warming is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, including the amount of rainfall associated with each tropical storm and hurricane.4 Princeville, like countless other places located on the water’s edge in coastal regions, is threatened by both oceanic storms and the delayed flooding caused by upstream precipitation. With increased rainfall, it is reasonable to expect that floods will become more frequent in Princeville and in vulnerable communities across the world. There is a call among preservationists to be nimble in the pursuit of the field’s basic beliefs and ideals, to prioritize, and to be realistic about which significant cultural landscapes can be preserved.

Within that call are assumptions worth examining. One is the singular urgency of historic preservation in the face of climate change. The traditional aim of historic preservation has been to identify important buildings and to freeze them in time; this static approach has always made the field an uneasy fit for important landscapes, which are living and inherently dynamic. Another assumption is that historically and culturally significant landscapes have been identified, and the daunting task ahead is to protect them. The darker reality is that climate change threatens to fundamentally alter or eradicate many of the significant places that have yet to be considered by traditional preservation groups.

In “Black Landscapes Matter,” Kofi Boone describes the “professional implicit bias towards privileged European landscapes,” which often “were funded and created through the domination of other peoples and landscapes.”5 Boone’s definition of significant landscape architecture includes the South Carolina plantation designed and built by enslaved West African rice farmers, the thousands of Rosenwald School sites, the campuses of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and black towns like Princeville.

In Princeville today, the only sites recognized by conventional historical designations are the Rosenwald-era Princeville School and the site of Freedom Hill. The school—now the Princeville Museum and Welcome Center—was listed in 2001 on the National Register of Historic Places, and a North Carolina highway historical marker was installed on Freedom Hill in 1988. The broader Princeville landscape is not the type to be lauded by traditional preservation advocates, who in the past have deemed various structures, places, and features within its boundaries ineligible for historical designation (Figure 3).

The majority of Princeville’s existing structures were built after 1999. Its landscapes include cypress–gum swamps along the Tar River, plus the yards and streetscapes designed during the past 150 years by unnamed residents and local officials. The significance of Princeville’s landscape lies in its ability to contain the memories of current and past Princeville residents, rather than in its formal design or physical artifacts. Scholarship on black cultural landscapes suggests that this memory-driven approach is better suited to understanding the significance of our country’s historically black spaces, built under the duress of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, threatened by flood and urban renewal, and often defined less by buildings and physical installations than by customs, stories, and events. Craig Evan Barton referred to these overlooked landscapes as “sites of memory.”6

Princeville’s sites of memory include Freedom Hill, where the earliest residents gathered to escape bondage and then to build their own town; Shiloh Landing, a bend in the Tar River where people were delivered into the brutal eastern North Carolina slave economy; Church Street, where children walked to school and ran from porch to porch; and the Tar River baptismal site, the spit of land below the bridge into Tarboro that was the destination of white-robed processions of local churchgoers from 1890 to 1950.

The National Park Service guidelines on significant landscapes are clear: Recent changes that have erased a landscape’s historic characteristics—a critical mass of old buildings or remnants of traditional, often agricultural, land uses—render a landscape ineligible. Where does that leave Princeville and places like it? Princeville’s cultural landscape is fluid by nature, grounded as it is in individual and collective memory and in the rebuilding heritage that has become part of Princeville’s cultural lifeway. That leaves the town as a whole with neither historical designation nor the attention and protections enabled by it.

Efforts to protect significant cultural landscapes from the effects of climate change must look beyond historic preservation to place equal emphasis on the urgency of heritage conservation—“heritage” referring to the lived experiences and cultural norms of a place, and “conservation” to the carrying forward of that socioenvironmental ecosystem through behavior, interaction, and custom. The vitality of Princeville’s living community and the protection and interpretation of its landscape offer the best possibilities for ensuring its survival and its relevance to future generations; the object-oriented lens of historic preservation is too limiting.

In Princeville after Hurricane Matthew, state and federal officials used GIS to generate a bevy of maps with layers of geospatial data to inform the recovery decisions of planners and engineers. One layer was called “Assets,” illustrated as purple dots on the map. The dots included the local Dollar General, but not Freedom Hill. Bennett Auto Sales was highlighted, but not Shiloh Landing. The Edgecombe County liquor store, but not the Tar River baptismal site. This is not to say that individual planners see Dollar General as a defining asset of Princeville, or that they fail to see the importance of Freedom Hill. But it matters that our tools are lacking. These are the instruments used to prompt action and inform decisions. It is alarming to think that the return-on-investment models used to justify disaster recovery spending might value Princeville as simply the sum of its 15-year-old buildings.

We need a different approach—one that acknowledges the social and cultural assets of places, that supplements technical expertise with local experience and intergenerational knowledge, and that prioritizes equally the preservation of objects and the conservation of place-based heritage.

Root shock

I could not actually imagine how the water could heap up like that. I wondered if it was like the Red Sea. I wondered how is it you’re saying you can’t go back to Princeville. I wondered how were we going to go forward.7

—Linda Joyner, commissioner, town of Princeville

On October 8, 2016, Hurricane Matthew dropped 20 inches of rain from North Carolina’s coast to the Piedmont region 200 miles inland. As water drained from cities and towns upstream, the Tar River swelled, and water began to enter Princeville from around the levee’s easternmost edge. By October 12, more than half of Princeville was under water.

According to a Salvation Army report8 published in 2011 and based largely on observations after Hurricane Katrina, the first phase of recovery immediately following a flood is Emergency Disaster Response, which lasts about 90 days and is concerned with primary care. The next phase, Assessment and Cleanup, spans the first 12 months after a flood. Its first priority is cleanup. The third phase, Strategy Development, typically begins six months after a flood and continues until Month 18. During this time, resilience, mitigation, and recovery plans are created or updated to reflect realities on the ground. Businesses and individual property owners begin making decisions about whether to rebuild. Trust between residents and public officials can be built or eroded. Eighteen to 36 months after a flood is Initial Implementation, the predevelopment and preconstruction phase of disaster recovery. Most of the federal government work—building partnerships and matching needs to capital allocations—is transferred to state and local agencies, and the private sector begins to rebuild.

Approximately 36 months after a flood is the Follow-Through Implementation phase. This marks the beginning of significant, publicly funded rebuilding and construction. It typically lasts until five years after the initial flood, and its scope is determined in large part by the availability of recovery dollars and the sustained attention of federal and private funders. As climate change increases the frequency and severity of weather-related disasters, recovery dollars and public attention are increasingly spread thin. When Hurricane Matthew inundated Princeville and other towns in 2016, the damage it caused made it the ninth-costliest hurricane in the history of the United States. Since then, Hurricanes Harvey, Maria, Irma, Michael and Florence each have surpassed Matthew’s damage and rebuilding costs. At the time of writing this article, it’s too early to estimate the recovery cost of Hurricane Dorian and other storms of the 2019 hurricane season.

Princeville’s experience after Hurricane Matthew has largely followed the timeline described in the Salvation Army report. Three years after the flood, the volunteer fire station had reopened, and some residents had rebuilt and returned. But Town Hall, Princeville Elementary School, Princeville Museum and Welcome Center, and Mount Zion Primitive Baptist Church were closed and awaiting renovation. A handmade sign on Freedom Hill reads: “Princeville Is Coming Back” (Figure 4).

When the clinical psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove interviewed African Americans whose families had been displaced by urban renewal, a federally funded movement that replaced their homes and neighborhoods with freeways and convention centers in the 1960s and 1970s, she used the term “root shock” to describe the sense of aching communal loss that followed.9 Fullilove wrote: “The cues from place dive under conscious thought and awaken our sinews and bones, where days of our lives have been recorded. Buildings and neighborhoods and nations are insinuated into us by life; we are not, as we like to think, independent of them. We are more like Siamese twins, conjoined to the locations of our daily life, such that our emotions flow through places, just as blood flows through two interdependent people. We can, indeed, separate from our places, but it is an operation that is best done with care. When a part is ripped away … root shock ensues.”

Fullilove argues that displacement is the defining problem of the 21st century; certainly one of the driving causes of displacement will be flooding and the growing threat of climate change. In America alone, according to the latest models that utilize updated data on river levels, rainfall, and population density, 41 million people live in the 100-year flood zone, areas with a 1% or greater probability of flooding in any given year.10 These updated models are calculated on past weather events rather than predictive climate models. Still, based on projected population growth alone, they predict that 15.8% of the US population will live in the floodplain by 2050. What can designers, planners, and conservationists do when faced with that magnitude of potential trauma?

We can begin by acknowledging the root shock that people and communities experience when the physical fabric of their lives is disrupted. Our current recovery processes rely too heavily on long-term plan-view proposals, opaque terminology, and rebuilding timelines that allow for years of absence, loss, and neglect in the landscape. The results in affected communities are predictable: planning fatigue, frustration, and despair of realizing a “new normal.”

There is a promising, supplementary approach to be found in diverse bodies of research. As a psychiatrist, Fullilove refers to the solution as “milieu therapy.” Civic ecologists refer to “urgent biophilia” or “greening in the red zone.” Whatever the term, the goal is to promote recovery by allowing people who have experienced place-based disaster to engage in the act of place-based cultivation—cultivation of relationships, of community, of positive emotions, and of the land.

In their book Greening in the Red Zone: Disaster, Resilience and Community Greening, Keith Tidball and Marianne Krasny compile powerful examples of this cultivation-oriented practice and its observed impact in restoring individual and community morale and resilience following disaster. Their examples include small-scale community gardening in post-war neighborhoods in Guatemala; tree-planting efforts in post-Katrina New Orleans; communal art and garden installations to reclaim a site of violence in post-apartheid Soweto, South Africa; memorial gardens and groves in post-9/11 New York City; bike trails and sites for cultural remembrance along the Berlin Wall corridor; and the establishment of cooperative, interethnic wildlife management practices in post-conflict northern Kenya. Tidball and Krasny argue that each of these efforts, by engaging survivors in asset-based planning and development, “restored the social–ecological balance in symbolic and real ways, all while creating positive feedback loops and virtuous cycles that trend towards desirable resilient states.”

Small and large, temporary and generational, these contextually appropriate, land-based interventions have been shown to build resilience and to help people heal. Their impact illustrates a need to supplement our abstract, top-down recovery processes with on-the-ground, community-driven, place-based practice.

A heritage-based approach to recovery

I want you to hear the scripture again. It says: ‘How can we sing the songs of the Lord in a strange land? If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its skill and may my tongue cling to the top of my mouth, if I do not consider Jerusalem, Jerusalem.’

I want to take the liberty and say, ‘If I forget you, Princeville, may my right hand forget its skill.’

To remember Princeville is to be a prisoner of hope…. Hope doesn’t merely come from emotion, hope comes from instruction. You have to know why you believe. In other words, the only way I can sing a song in a strange land is to remember. That’s intellectual. To remember Jerusalem, to remember what I’ve come through.11

—Rev. Dr. William Barber II, president, Repairers of the Breach

In spring 2017, about six months after Hurricane Matthew, the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab (CDDL) in the North Carolina State University College of Design received funding from the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory to produce guidebooks for six eastern North Carolina towns that faced flooding after Matthew. These books, titled Homeplace, were intended to help residents and officials of these mostly small and rural towns navigate recovery jargon and imagine how high-quality rebuilding could unfold at the home, neighborhood, town and regional scales.

One of the six towns was Princeville. As the Homeplace project concluded, CDDL faculty learned that the state of North Carolina was considering the purchase of a 53-acre parcel located above the floodplain and just outside the Princeville town limits. The idea was for the town to annex the property and move homes and essential services there. The College of Design joined the Hurricane Matthew Disaster Recovery and Resilience Initiative and North Carolina Emergency Management in organizing a five-day workshop to help Princeville residents consider their options. Designers, planners, preservationists, and experts in economic development and disaster recovery flew in from across the country to participate.

It was clear from Day One that Princeville residents placed a high priority on maintaining a meaningful connection to their landscape. There was limited interest in moving the elementary school or the town hall to higher ground. Many people could describe with precision which lots held which houses belonging to which families, and when asked to name their most loved landscapes, residents sometimes pointed to apparently empty lots where there once had been a beloved convenience store or meeting place.

Design faculty saw during the workshop that there were spatial and temporal gaps in the Princeville recovery efforts and no obvious institutional partner to fill them. The spatial gap was that the land most valued by Princeville residents and supporters as containing sites of memory was the very land least valued by recovery officials, given its location in the floodplain and its relatively low value as real estate. The temporal gap was the rebuilding timeline, which promised a good deal of behind-the-scenes action for three years but almost no action within the landscapes where Princeville residents felt such a strong sense of place.

CDDL and its faculty partners began a flexible, open-ended partnership with the town of Princeville to explore methods of filling the gaps. The college has listened to town officials’ expression of their needs, supported the planning efforts of recovery officials, and joined or convened other institutional partners with expertise and resources outside the norm for recovery work. Partners have included the North Carolina Museum of History, the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission, the North Carolina Rural Center and the Upper Coastal Plain Council of Governments.

The result of the college’s listening posture has been a combination of short-term, visible work on the ground and long-term planning and strategy. Short-term work has been implemented largely independently of the Princeville recovery process, with volunteer labor and minimal funding support. The goal of this work is to mark histories and establish concrete symbols of ongoing life and progress as slower recovery and rebuilding processes play out. Efforts are intentional, incremental, and guided by plans co-created with community leaders to create cumulative impacts.

In April 2019 volunteers from Princeville and NC State planted a garden of white- and blue-blooming trees, shrubs, and perennials in front of the still-shuttered Town Hall (Figure 5). Cars driving by honked in appreciation, and the volunteer fire department committed to water the plants regularly with the fire engine hose. In August, NC State’s summer design-build studio unveiled a Princeville mobile museum—an exhibit of historical photos and stories housed in a bespoke, moveable trailer. That same month, a year’s worth of faculty effort and fundraising culminated in the unanimous vote by town commissioners—and approval from the state Department of Transportation—to post long-overdue highway signs that announce Princeville’s historic designation at the town’s four primary gateways. Another faculty member worked in the summers of 2018 and 2019 with local youth and a Princeville nonprofit to design a route and signage for an interactive, landscape-based Princeville Walking Tour.

All of these efforts grew from conversations with town officials and residents, and from a growing sense of the things held important by Princeville but not addressed within standard recovery work. They reflect a willingness by the college and its partners to step outside of traditional disciplinary boundaries in order to serve the immediate emotional needs of a displaced community.

The long-term plans and proposals are intended to supplement and be implemented in coordination with Princeville recovery work. They include land conservation, greenway, blueway,12 and placemaking proposals to help the town meet its goals for revitalization and a tourism economy, and to ensure the long-term protection and interpretation of the town’s sites of memory. These proposals require stronger organizational partnerships and more substantial funding support, but they build on the installation and interpretation work of the short-term interventions. And unlike too many recovery plans, they are carefully crafted to reflect Princeville’s assets as seen in the eyes of its past and current residents.

Princeville has a singular history as the oldest black town in America, but it’s like many other places in the country that are both vulnerable to natural hazards and under-valued within our standard disaster recovery frameworks. As more communities face climate-induced disasters and the need to rebuild—or in extreme situations the need for partial or full relocation—it will take the concerted effort of people and institutions outside of recovery agencies to identify the human needs not being met and to devise community-driven, discipline-blurring, place-based responses that reveal the meaning(s) embedded in the communal landscape. Especially in historically marginalized communities, we have an obligation to recognize the power of place and to ensure our post-disaster response is robust enough to recognize it as well. Our hope is that CDDL’s work with Princeville starts a conversation about the role of the post-disaster landscape as a vehicle for memory, healing and cultivation, prompting immediate and multidisciplinary action to supplement the efforts of recovery agencies.

Lindsey Naylor, Design Workshop, Inc.

Virginia Fall, GroundLevel, Inc.

Andrew Fox, North Carolina State University

Corresponding Author:

Andrew Fox

Department of Landscape Architecture

North Carolina State University College of Design

Campus Box 7701

Raleigh, NC 27695

andrew_fox@ncsu.edu

Endnotes

1. Remarks delivered by Lanier at the Princeville Design Workshop, August 25, 2017.

2. Blue, “Reclaiming sacred ground: How Princeville is recovering from the flood of 1999.”

3. Melnick, “Climate change and landscape preservation: Rethinking our strategies.”

4. Paerl et al., “Recent increase in catastrophic tropical cyclone flooding in coastal North Carolina, USA: Long-term observations suggest a regime shift.”

5. Boone, “Black Landscapes Matter.”

6. Barton, Sites of Memory: Landscapes of Race and Ideology.

7. Remarks delivered by Joyner at the Princeville Design Workshop, August 25, 2017.

8. Jonker, Miller, and Brechwald, “EnviRenew Resilience Part 1 Report: Creating resilient communities.”

9. Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It.

10. Wing et al., “Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States.”

11. Remarks delivered by Barber at the Princeville Day of Hope event, September 30, 2017.

12. Blueways are designated water trails located on navigable waterways of regionally significant rivers and their contributing watersheds that enable economic, recreational, and ecological opportunities for the communities that reside along their path.

References

Barton, Craig Evan, ed. 2001. Sites of Memory: Landscapes of Race and Ideology. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Boone, Kofi. 2017. Black landscapes matter. Ground Up 6(1): 8–23.

Blue, Victor E. 2000. Reclaiming sacred ground: How Princeville is recovering from the flood of 1999. NC Crossroads 4(3).

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. 2016. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New York: New Village Press.

Jonker, Lindsay, Alexandra Miller, and Dana Brechwald. 2011. EnviRenew Resilience Part 1 Report: Creating resilient communities. The Salvation Army (March).

Melnick, Robert Z. 2015. Climate change and landscape preservation: Rethinking Our strategies. Change Over Time 5(2): 174–179.

Paerl, Hans W., Nathan S. Hall, Alexandria G. Hounshell, Richard A. Luettich, Karen L. Rossignol, Christopher L. Osburn, and Jerad Bales. 2019. Recent increase in catastrophic tropical cyclone flooding in coastal North Carolina, USA: Long-term observations suggest a regime shift. Scientific Reports 9(1): 10620.

Tidball, Keith G., and Marianne E. Krasny. 2014. Greening in the Red Zone. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Wing, Oliver E.J., Paul D. Bates, Andrew M. Smith, Christopher C. Sampson, Kris A. Johnson, Joseph Fargione, and Philip Morefield. 2018. Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States. Environmental Research Letters 13(3): 034023.